Diminished 7th Chords

DIMINISHED 7th CHORDS

Diminished 7th chords are some of my favorite chords because they’re just so amazing and versatile! I would like to show you how to form a diminished 7th chord, and how they can be used.

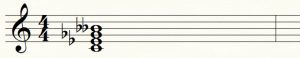

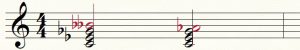

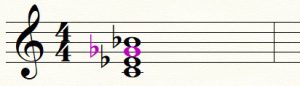

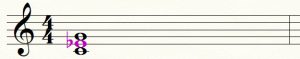

Diminished 7th chords are formed by starting with a diminished triad (root, flatted third, and flatted fifth) and then a double-flatted 7th…

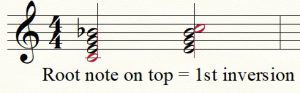

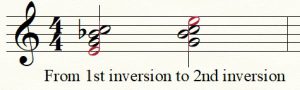

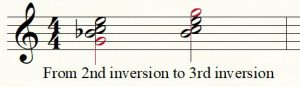

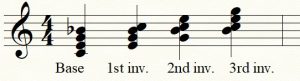

If you play each of these notes on the keyboard, you can see that there are three half-steps between each note. This is the only chord in existence that has equal spacing between each of the notes in the chord. (Note that on the piano, you are playing an ‘A’, though because the chord is stacked in the 1-3-5-7 format as it should, the proper name is B-double-flat). Even if you extend the chord upwards, it still follows the same note pattern by three half-steps, which could go on forever up the keyboard. This means that the chord can sound essentially the same, and serve the same function in music, regardless of which “inversion” it is in…

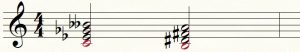

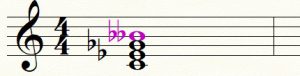

Because each of the notes are three half-steps away from each other, there are really only three diminished 7th chords in existence. You can make a diminished 7th chord starting on the notes C, C#, or D, but then when you start on E flat, you are back to the same chord you had with the root of C… (See the image below). Likewise, when you start a chord on E, it is the same chord as was started on the root of C#. And again, when starting with a root note of F, it is the same chord as was started with the root of D. So really there are just three diminished 7th chords that can change root position all the way up the keyboard….

Notice that the last chord here, starting on the E flat, is made from the same notes as the first chord which started on C. So, it is basically the same chord in a different inversion.

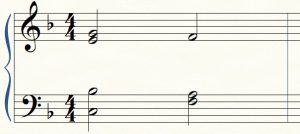

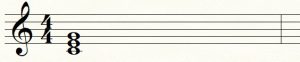

The other amazing thing about a diminished 7th chord, which makes it so useful, is that if you drop any one of the notes of that chord, you automatically create a dominant 7th chord. Let’s look at the C diminished 7th chord… When you drop the C by a half step, you have a B7 chord.

For clarity’s sake, I stacked the B chord so it is easier to read. But the red notes in the image are the only ones that changed! Because of enharmonic naming, the black notes really create the same sound whichever way you write them. The E flat and D sharp are the same tone, the G flat and F sharp are the same tone, and the B double-flat and A are the same tone.

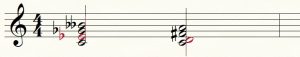

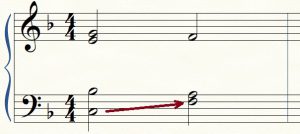

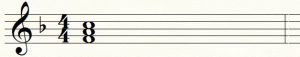

Now, if you were to start with the C diminished 7 chord and drop the E flat by a half step, you would have created a D7 chord, in 3rd inversion.

If you drop the G flat by a half step, you have created an F7 chord, in 2nd inversion…

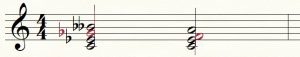

And if you drop the A by a half step, you have created an A flat 7 chord, in 1st inversion.

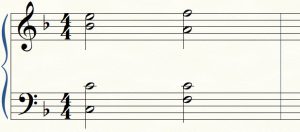

From each of these V7 chords, you can then move easily into a I chord quite naturally. As we had previously learned about dominant 7 chords, they have a strong tendency to resolve to a I chord. So, when we created the B7 chord, the next chord we instinctively feel should come would be an E chord. When we created a D7 chord, we can resolve that to a G chord. When we created the F7 chord, it resolves to a B flat chord. And when we created the A flat 7 chord, it resolves to a D flat chord. If you’re still confused, review this post about dominant seventh chords to help you out!

Hopefully you can see how useful these diminished 7th chords can be, especially when trying to create modulations for key changes in your music. Since there are basically only three diminished 7th chords possible, and you can create 4 dominant 7th chords from each of them, it is a simple way to lead to key changes in your music! I hope you now appreciate the beauty and versatility of diminished 7th chords as much as I do!

And the beat goes on…

You must be logged in to post a comment.